El Niño winters are generally known for being mild with low snowfall in the PNW. To date, the 2023-24 winter has been consistent with those expectations. Fortunately, some more favorable news came out last week that may have an impact on our weather in the months ahead.

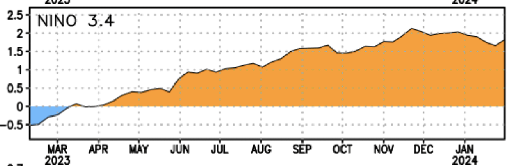

The NOAA Climate Prediction Center made news last week by issuing a La Niña Watch, meaning that conditions are favorable for a La Niña to form in the next 6 months. This may come as a bit of a surprise given the current sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the equatorial Pacific, which have hovered around a + 2°C anomaly in the “3.4” region in which El Niño and La Niña conditions are commonly assessed.

The widespread warmth is easy to spot on a global SST anomaly map.

It’s not just the Pacific either, the global SST anomaly has been smashing all-time daily records for nearly a year.

Changes on the way

While surface ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific remain warm, sub-surface anomalies have begun to cool off, an early sign that El Niño is waning. Additionally, most models predict that the ENSO index will drop to neutral by summer and into La Niña territory by fall.

NOAA currently has the probability of La Niña conditions around 75% by fall, which would strongly suggest that the 2024-25 winter would end up in La Niña territory.

It is worth noting that these models can be wrong and historically have shown their worst performance in the spring months. We also have no idea if the potential La Niña will be weak, moderate, or strong.

Abysmal snowpack this winter, potentially better next winter?

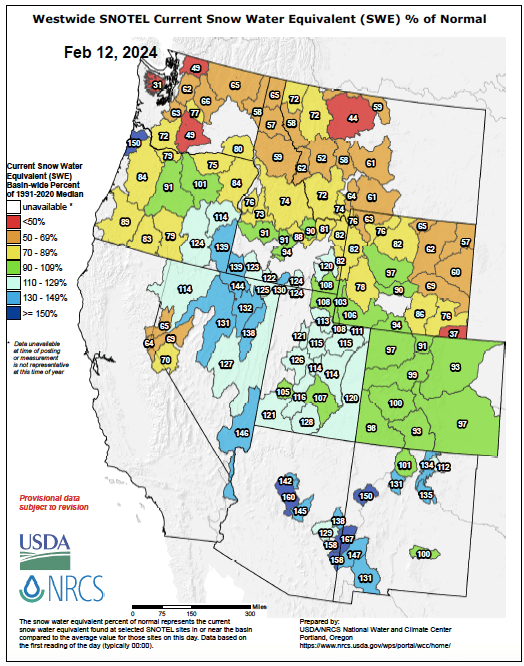

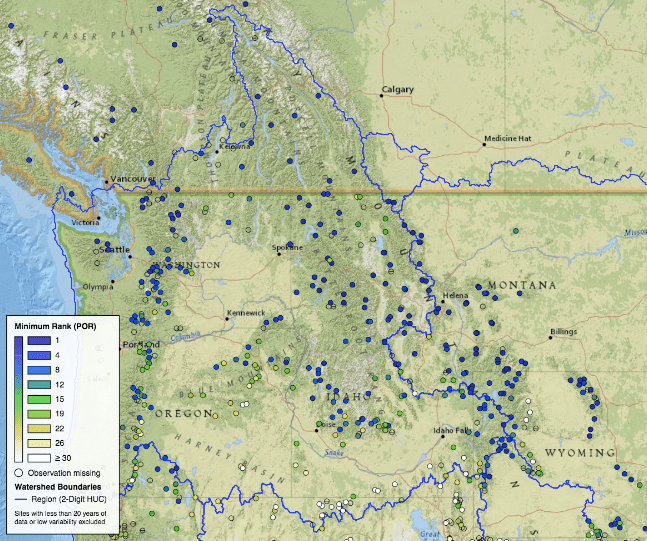

It is no surprise that snowpack this winter is running far below normal in Washington, northern Idaho, and Montana. The situation is generally better the farther south one looks, except for the Sierra Nevada.

The “percent of normal” map above can be a little deceptive, since many sites tends to stay within +/- 30% of normal by late in the winter. The map below shows the “minimum ranking” of snow water equivalent for the period of record, which is 30-40 years for most SNOTEL sites. A large number of sites are ranked in the top 5 least snowiest on record for the date, with many Montana sites at their lowest snowpack on record for the date.

In Washington, most of the sites in the Olympics and North Cascades are ranked #2 or #3 least snowiest during the period of record. The unprecedented 2015 year remains safely in the #1 ranking, while this year is running similar to 2001 and 2005.

The central and southern Cascades are in slightly better shape, with Paradise and Stampede Pass both ranked #8 least snowiest out of the past 42 years.

Winter temperatures and snowpack in the PNW are strongly correlated with ENSO

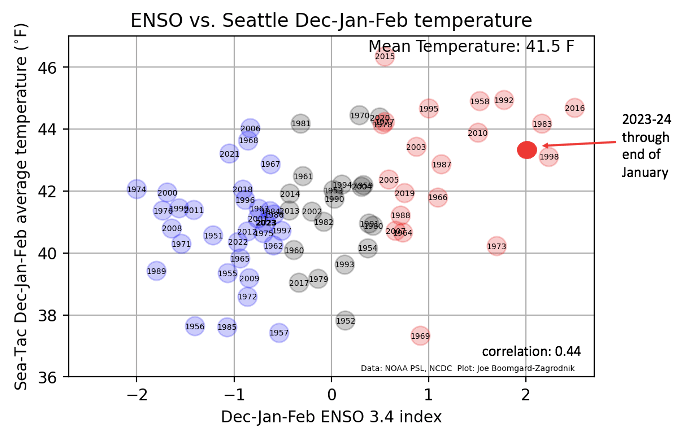

Seasonal weather prediction is often wrong, but one of the safest bets in the PNW is that El Niño winters will run warm with low snowfall and La Niña winters will run cold and snowy. Here’s a plot of the ENSO 3.4 index vs. Seattle’s average winter (Dec-Jan-Feb) temperature. Red dots are El Niño winters, blue dots are La Niña winters. The correlation is incredibly high and this winter is no exception.

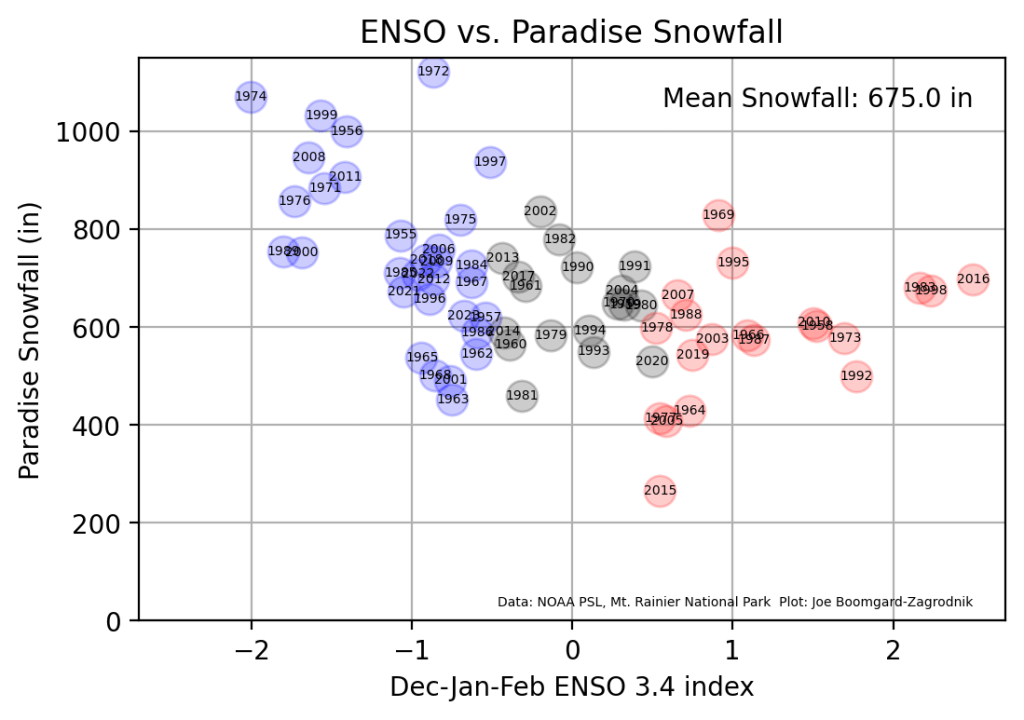

Total snowfall at Paradise (as measured by the National Park Service) shows a similar anti-correlation (-0.47).

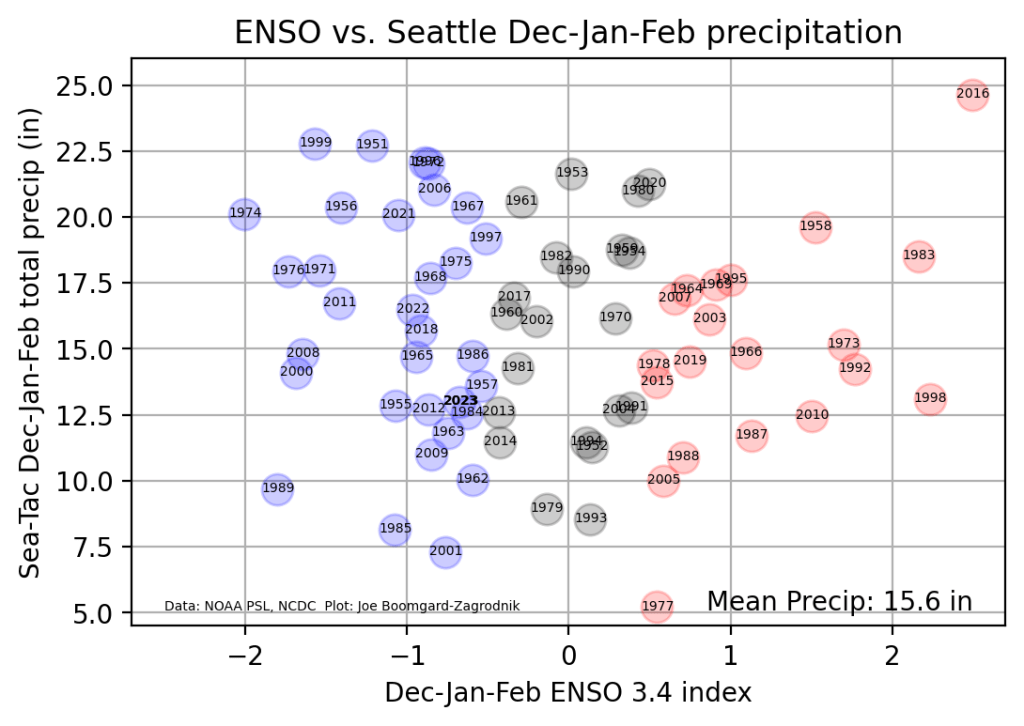

Interestingly, precipitation in Seattle has almost no correlation with the ENSO index. Sea-Tac has recorded around 13 inches of precipitation since December 1 as of this writing, which is slightly below normal.

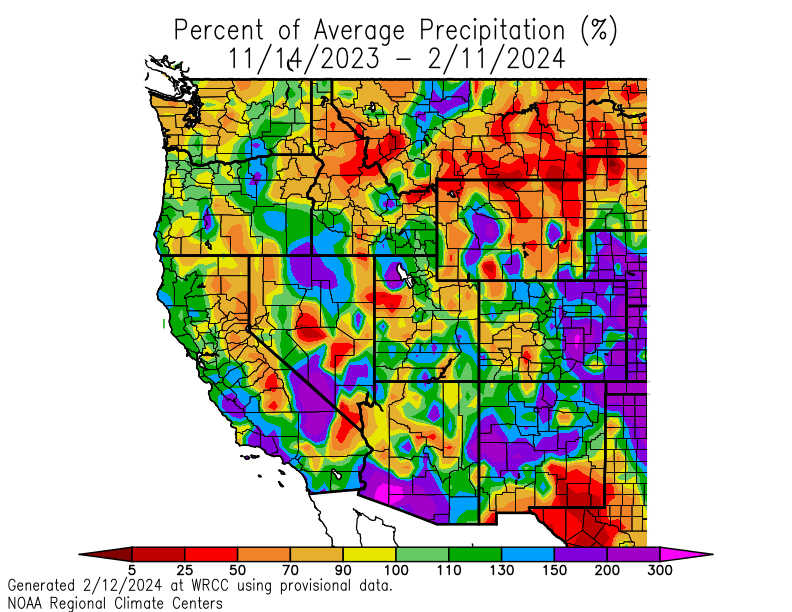

Precipitation over the last 90 days has been well below normal, which is contributing to the snowfall deficits, especially in Montana.

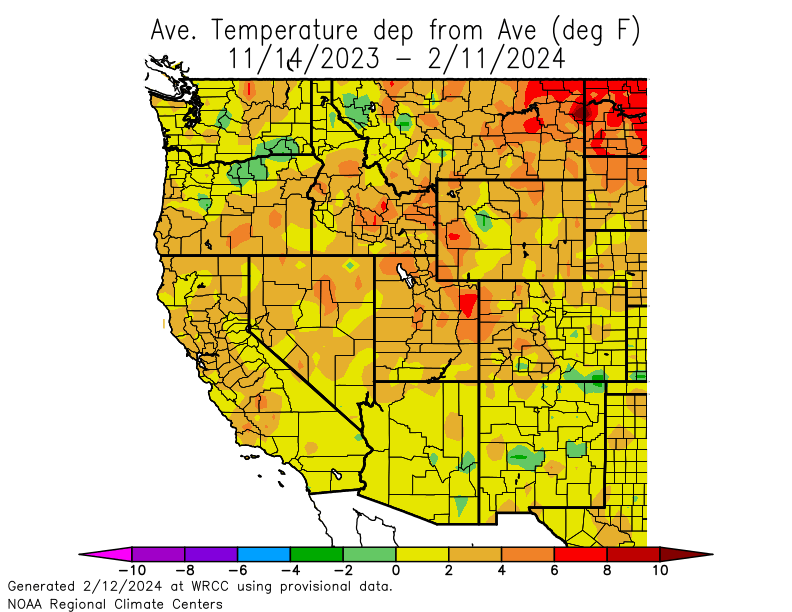

Temperatures over the past 90 days have been running near or above average nearly everywhere in the western US, which seems to be the case more often than not in recent years. Other parts of the US have been running more extreme warm anomalies this winter.

What is the role of climate change?

The conditions leading to low snowpack in the PNW are not particularly complicated — an El Niño winter combined with below-average precipitation is a common recipe for the conditions we are experiencing this year. Snowpack is also especially low even for the low standards of typical El Niño winters.

In addition, global ocean temperatures are running well above previous records and the combination of the warmth in our region along with the warmth across much of the rest of the planet is clearly a result of climate change.

The post below by Andy Hazelton shows how much warmer the global SST anomalies look in 2024 compared with two recent years that featured an El Niño transition to La Niña — 2010 and 2007.

So there is clearly reason to be concerned by these trends and it is important to recognize that current conditions are a result of natural cycles superimposed on a significant warming trend.