Summary: YES, early season snowpack has declined recently, even as season total snowfall and melt out dates remain essentially unchanged. Read on to learn more…

In my previous post I showed that snowpack in Washington State is at or near record lows for early December at a number of sites while at the same time near a record high at Harts Pass in the North Cascades. Let’s review:

Stampede Pass (3850 ft, central WA Cascades) — record low:

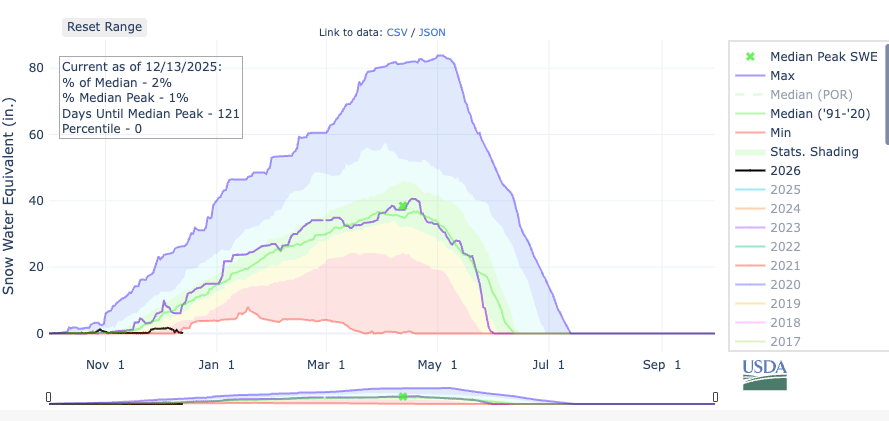

Paradise — 5150 ft — central WA Cascades — record low:

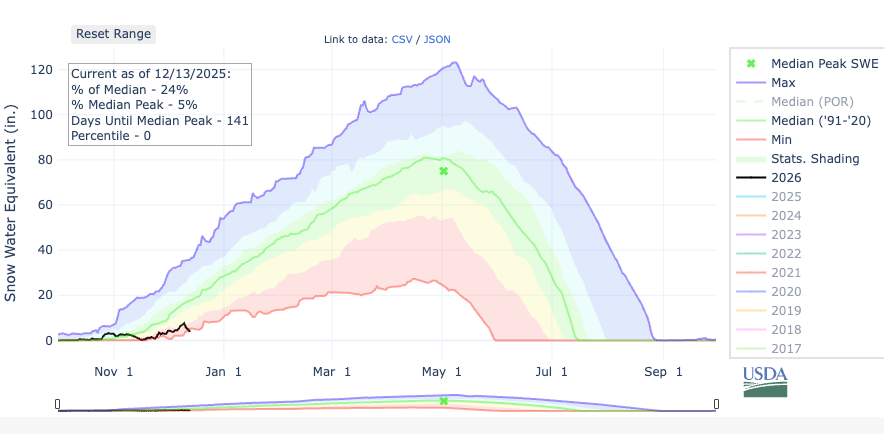

Harts Pass — 6490 ft — north WA Cascades — 161% of normal, 98th percentile:

The above example perfectly encapsulates the challenge of generalizing snowpack trends with a changing climate. As the global climate warms, increasing moisture and precipitation can result in additional snowfall — as long as the temperature remains below freezing. If the temperature fails to drop below the critical 0°C/32°F threshold then the additional precipitation becomes detrimental to snowpack and instead leads to more problems with flooding.

It’s easy to imagine this complexity on a big mountain like Mt. Rainier. If winter temperatures and precipitation increase, the top of Mt. Rainier might be expected to experience more snowfall, while the lowest elevations might experience less. The seemingly simple question of whether the mountain as a whole would experience more or less snow is actually difficult to answer.

It doesn’t help that snow is one of the most challenging climate indicators to work with. Snow is difficult to measure, highly variable in both time and space, and has few reliable records prior to the 1990s. At the same time, snow is synonymous with climate change in the public sphere. Pictures of bare ski resorts like Snoqualmie Pass (below) were all over the local news this week.

The most ironic part of the picture above might be the sad-looking snow guns with their tiny little piles of snow. Snowmaking requires dry air to be effective and is helpless in a warm+wet weather pattern.

Back to the question at hand. With all of the disclaimers aside, does the actual data suggest any change in snowpack trend over the past 40 years?

Is there any trend in Washington State snowpack?

For this analysis, I pulled the daily SNOTEL data from four Washington State sites that have records going back to the mid-1980s:

- Stampede Pass (1983-84 to present) –3850 ft elevation

- Paradise (1984-85 to present) — 5150 ft elevation

- Spirit Lake (1985-86 to present) — 3520 ft elevation

- Harts Pass (1983-84 to present) — 6490 ft elevation

I will consider Paradise and Harts Pass to be “high elevation” sites (> 5000 ft). Stampede Pass and Spirit Lake are “low elevation” sites (3000-4000 ft).

More information on SNOw TELemetry (SNOTEL) observations can be found in this great article by Jake Hartter at the Western Slope Conservation Center.

The variable most widely reported from these sites is the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE), which is reported as the depth of liquid water (in inches) contained within the snowpack. The SWE data comes from the weight of the snowpack on the snow pillow in the image above.

Any snow that melts will drain off of the snow pillow, so it is also helpful to compare with the precipitation gauge. The precipitation gauge is a weight-measuring sensor as well — everything that falls from the sky over the winter is collected in that big cylinder.

Overall snowpack trends

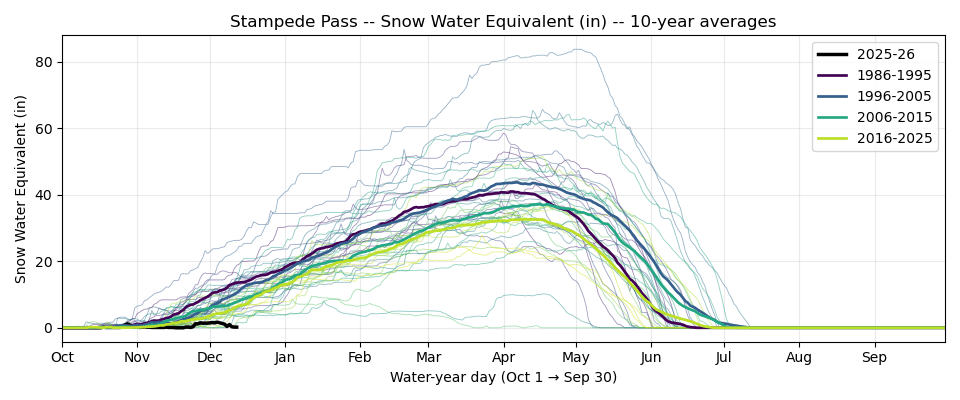

The overall snowpack results are plotted in four groups: 1986-1995, 1996-2005, 2006-2015, and 2016-2025. The years represent the end of the Oct-Sep water year, so “2025” means the 2024-25 winter season.

Stampede Pass shows what we might expect given climate change — snowpack across the entire water year is trending lower.

However, the trend at Spirit Lake (near Mt. St Helens) is not nearly as clear. Fall snowpack appears to have declined, winter snowpack is somewhere in the middle, and spring snowpack has increased.

The higher elevation sites both have upward trends in snowpack of around +0.1 in/year for the peak.

Length of the snow season

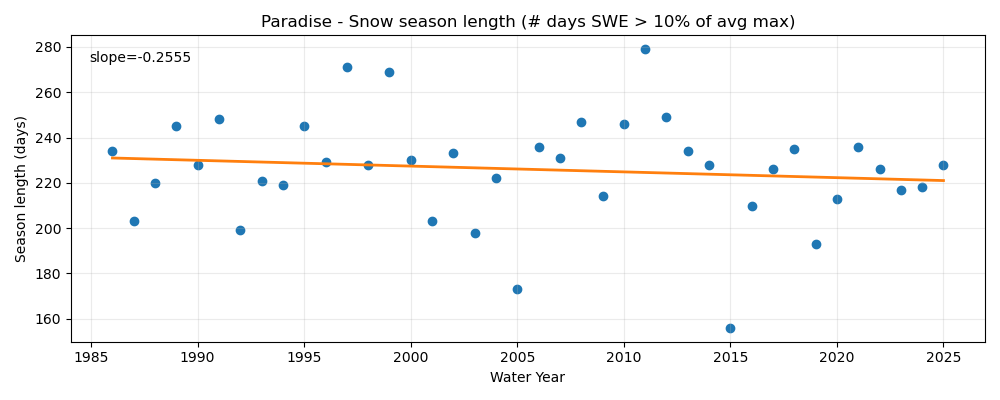

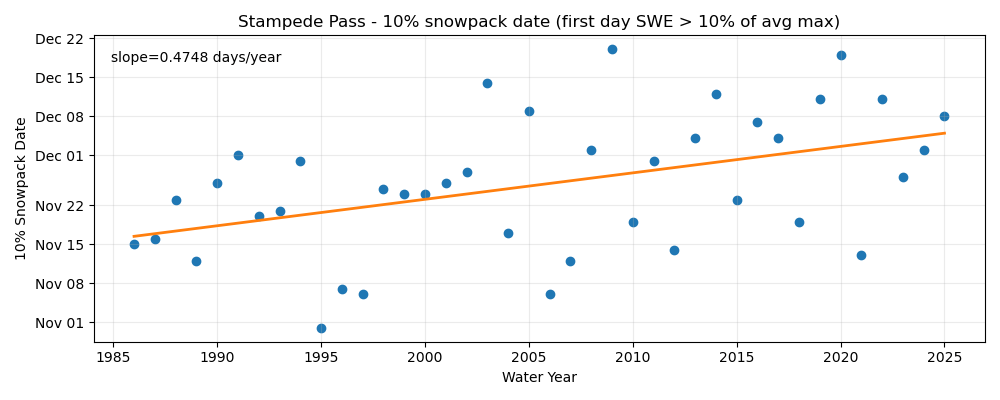

In some cases it looks like the trends at the beginning/ending of the season behave differently than the peak SWE. I defined the length of the snow season as the number of days between the first and last dates that SWE exceeds 10% of the annual average peak (using all 40 years for the average).

By this length metric, the snow season at Stampede Pass is declining by about 6 days per decade.

Spirit Lake is experiencing the opposite trend — longer snow seasons. However, the trend is asymmetric, with snow season starting later in the fall (trend: 3 days later per decade) and ending much later in the spring (trend: 11 days later per decade).

Based on the above, one might expect snow season length to be increasing at the higher elevation Paradise and Hart’s Pass sites. Instead, it is declining slightly at Paradise (2-3 days/decade) and is essentially flat at Hart’s Pass.

At both Stampede Pass and Paradise, the loss in snow season length is coming entirely from the fall. There has been no trend in meltout date at either station.

At Stampede Pass, the average snow season beginning date has moved back a whopping 19 days on average since the mid-1980s, from approximately November 16 to December 5.

At Paradise, the average snow season beginning date has moved back 11 days since the 1980s, from approximately November 19 to November 30.

Less snow in fall, more in spring?

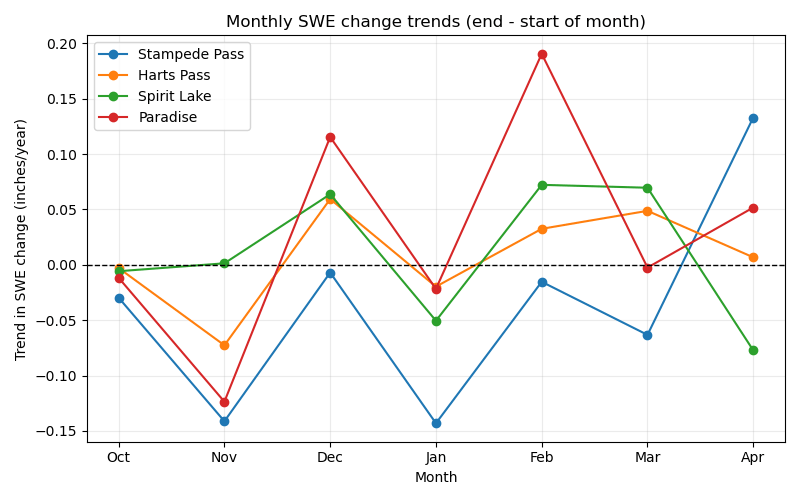

To dig a bit more into the interesting finding that fall snowpack is declining, here’s the trend in monthly snowpack accumulation (SWE at end of month – SWE at start of month) broken down into individual month.

October and November are clearly downward (except at Spirit Lake), but January is as well. December and February appear to be the best months to gain snowpack of late.

The above plot hints that there might be slightly more to the story than a simple fall vs. spring dichotomy. Let’s take a look at the precipitation trends as well.

It turns out that November and January have just been trending drier. I have a feeling this pattern is a result of trying to fit trends to single months over a relatively short time range, as there’s no reason to think that the drier November trend would be based on anything other than natural variability (random luck).

October is the only month that produces something that does look like it could be climate related — a decrease in snowpack despite a corresponding increase in precipitation. As one might expect, when temperatures for snow are marginal in the early season, increasing precipitation doesn’t lead to increased snowpack like it does in the middle of winter.

I attempted to make similar plots for temperature, but there was too much missing data to trust the result. It seemed like there was essentially no trend in wintertime temperature at these locations.

Big picture: colder and wetter winters produce more snowpack

The monthly breakdown above suggests that cold season precipitation is highly correlated with snowpack. Comparing the peak annual snowpack to total winter precipitation at Paradise shows a clear and obvious correlation.

Temperature shows a similar inverse trend, colder = snowier. Note again that the 1980s are missing entirely and some other years are missing data at times.

Note that recent years (yellow colors) do not show a strong propensity to trend one way or the other. These same patterns are apparent at the other three sites as well.

Final thoughts

Based on these 4 SNOTEL sites, Washington State had been trending toward a later start to mountain snowpack season in recent decades, especially at Stampede Pass. For now, wintertime snowfall, especially in December and February, has been making up for the late start, and the end of snow season shows little change.

The late snow season starts can probably be explained by some combination of climate change and random luck. If precipitation in November reverts to the longer-term normal, we might expect some earlier starts to snow season in the future. However, the decline in October snowpack is unlikely to reverse.

I found this asymmetric trend in snowpack to be a bit of a surprise. It has been previously reported that overall snowpack is generally unchanged in the PNW over the past few decades. Based on my analysis, it’s hard to argue with the conclusion reached by Nick Bond, Cliff Mass and others that overall snowpack hasn’t changed much, even if some sites are trending slightly upward and others are trending slightly downward. For now, it appears that even the lower elevation (3,000-4,000 ft) sites appear to be generally maintaining their peak snowpack, at least in the Washington Cascades.

The clear relationship between winter average temperature and seasonal snowfall at Paradise presents a warning sign — as temperatures continue to increase from climate change, we are eventually going to start seeing clearer trends in declining snowpack. The recent atmospheric river event was perhaps an example of that, since heavy precipitation was clearly NOT correlated with an increase in snowpack over the past week or two.