The cold and snowy period came to an end for most, but not all of the western Washington lowlands on Sunday as a strong frontal system delivered heavy rainfall along with snow in a few spots. The areas receiving snow were many of the usual favored spots for marginal lowland snow events including parts of Kitsap county and much of the King/Snohomish County foothills between I-90 and US-2.

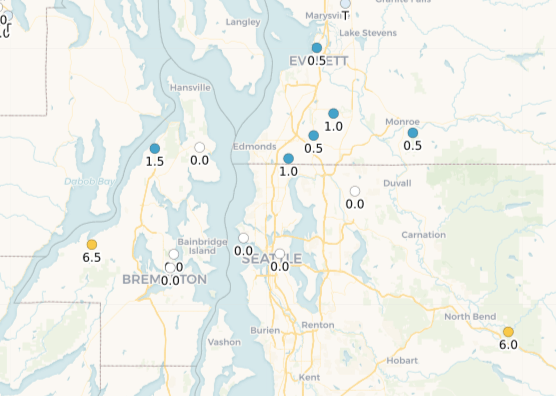

CoCoRaHS snowfall observations showed 6.5 inches near Seabeck on the Kitsap Peninsula (including thundersnow!), 6 inches near North Bend (up to 10″ in spots according to social media), and around an inch in the I-5 corridor around Lynnwood/South Everett. Social media reports suggested that Woodinville, Snoqualmie Ridge, Duvall, and other parts of the foothills received at least 3-4 inches of snow as well.

What was the forecast?

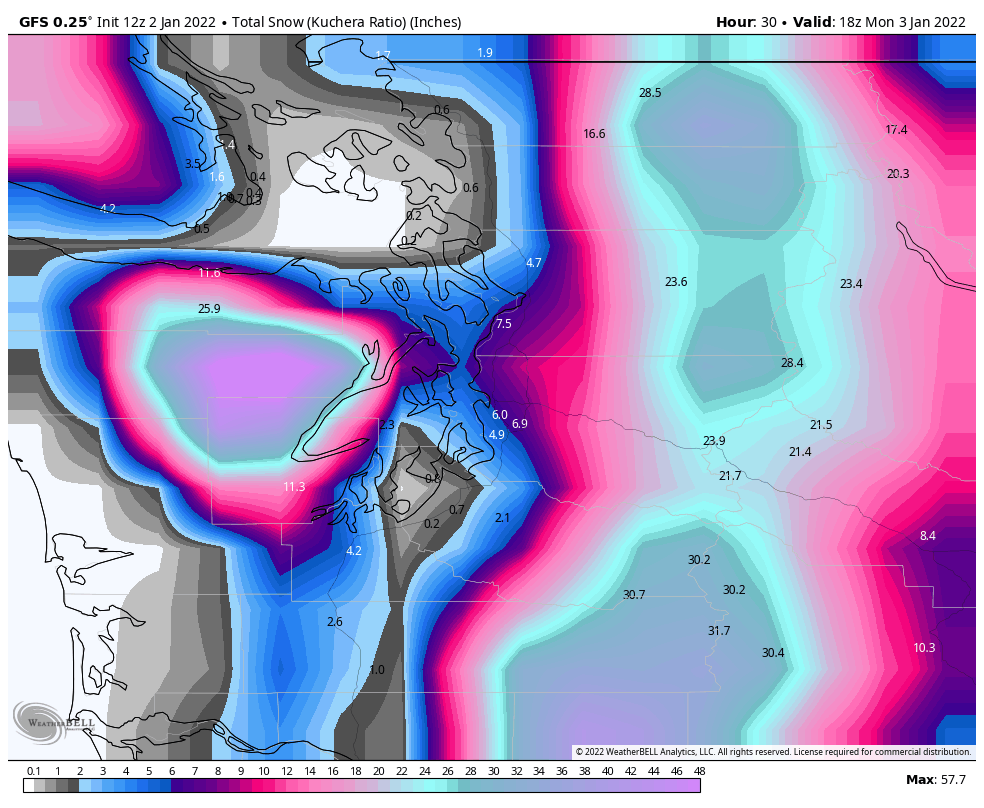

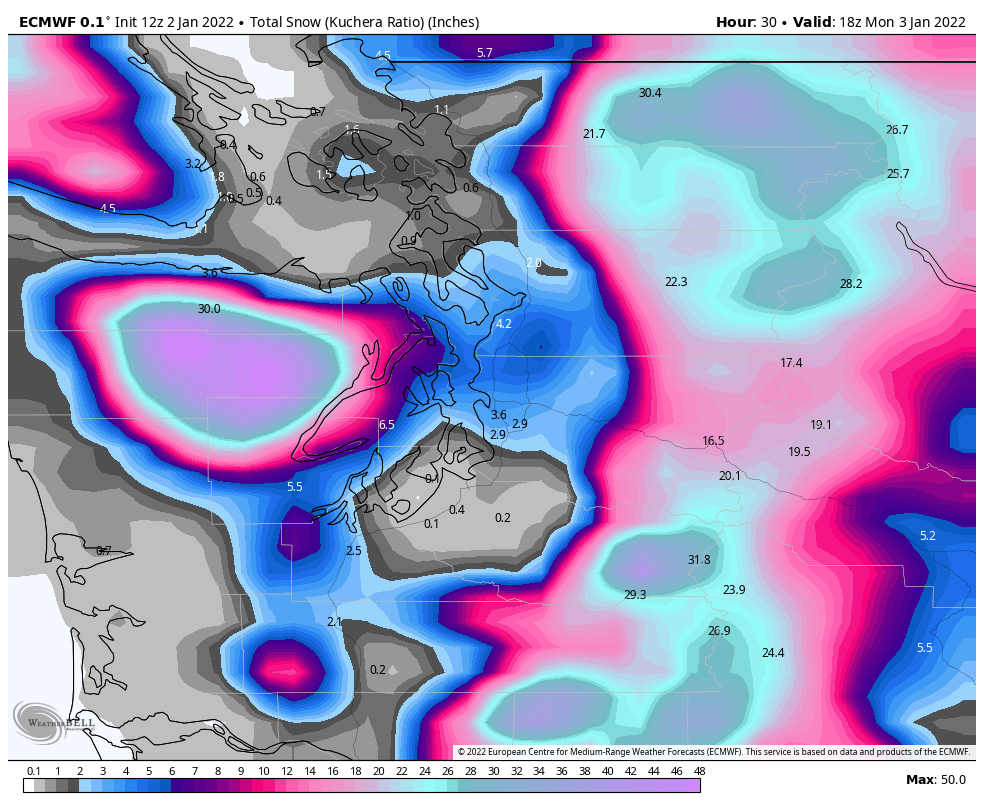

Yesterday’s 12 UTC runs of the global models (GFS and ECMWF) both incorrectly showed several inches of snow (Kuchera method) falling across the central Sound by Monday morning, including Seattle.

The 4/3 km UW-WRF (initialized at the same time as above) showed a snow level around 1,500 ft except for a correct forecast of snow in portions of Kitsap County. The WRF failed to pick up on the lower snow levels in portions of King and Snohomish Counties.

The HRRR model (initialized at 5 PM last night) was probably the most accurate as a whole at gauging where the rain/snow boundaries would be, but the amounts were underestimated in the lowland areas that did receive snow. Earlier runs of the HRRR had even less snowfall.

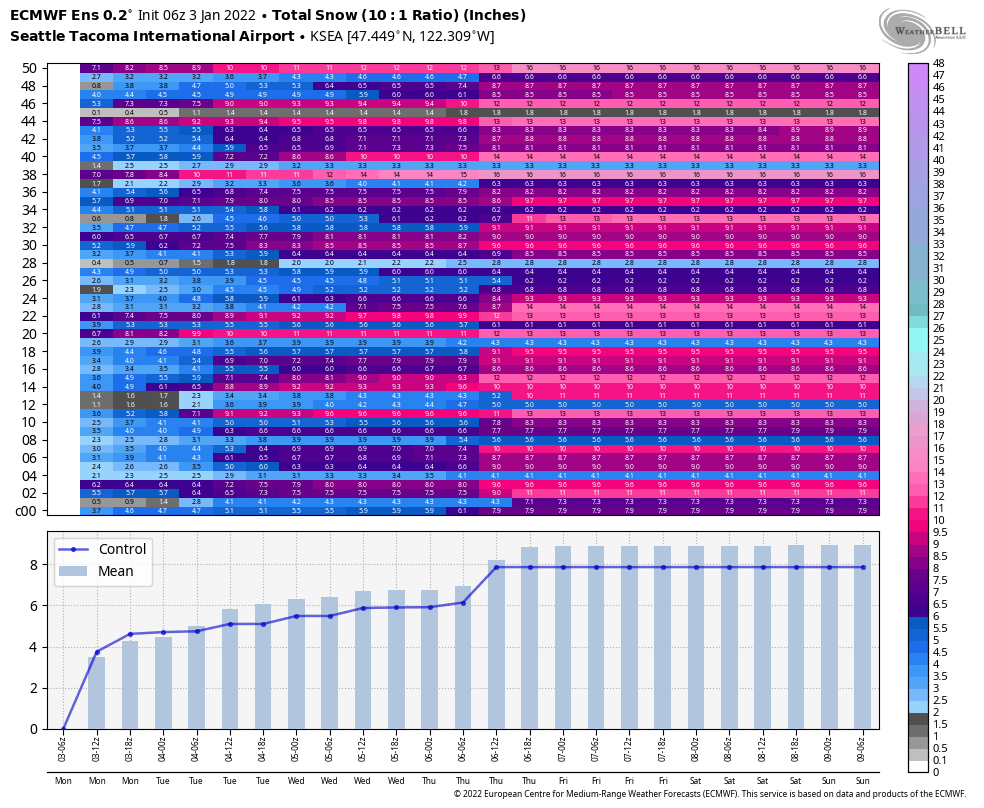

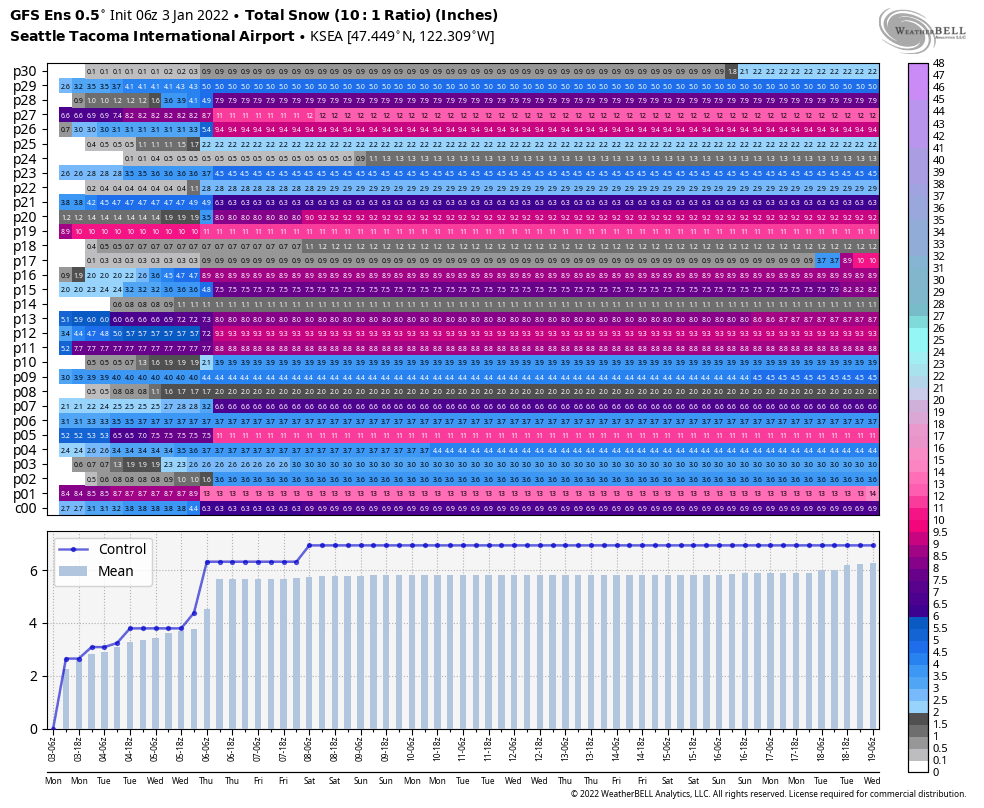

What about the global ensembles? The 06 UTC (10 PM) run of the ECMWF ensemble last night had an average of 4 inches of snow at Sea-Tac airport. Sea-Tac did not report any snow during this event.

The GFS ensemble at 06 UTC (again, when it was already obvious that snow was not going to materialize at Sea-Tac airport), was a bit better, with about half of the members correctly recognizing that no snow was going to fall overnight at the airport.

The NWS and local TV meteorologists predicted minimal snow in the lowlands and in some cases had to adjust their forecasts yesterday evening as snow reports started coming in at lower elevations than expected. The NWS made the following update at 6:15 PM Sunday:

KIRO meteorologist Morgan Palmer also recognized the possibility of lower snow levels in the afternoon, especially north of Seattle.

So it is fair to say that nobody got this forecast perfectly correct, but the professional meteorologists were correct to dismiss the global models showing several inches of accumulating snow in Seattle. They also were quick to adjust their forecasts as the storm moved in on Sunday afternoon and evening.

What made this forecast so difficult?

At first glance this storm looked way too warm for snow. Forecast 850 hPa (~5000 ft above sea level) temperatures were only in the -1 to -2 °C range, much warmer than the usual -6 °C threshold that we need for lowland snow in this region.

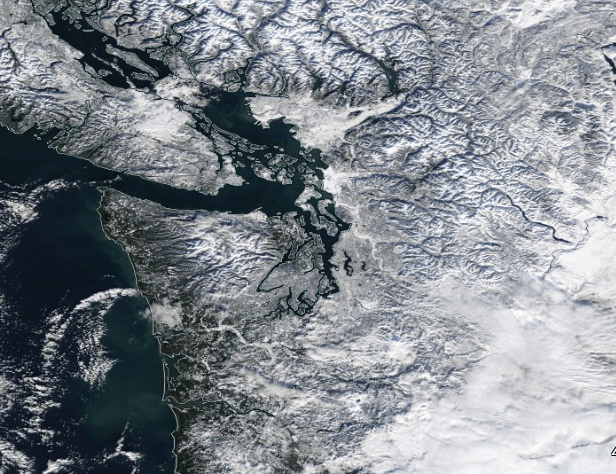

However, as of Sunday morning, near-surface cold air from the recent cold wave was still hanging around. Here’s what the region looked like from space on Friday afternoon. Snow melt on Saturday was minimal in the interior, so most of this snow was still around on Sunday morning.

On Sunday morning, a warm front pushed through the region, causing temperatures to quickly jump in to the upper-30s to low-40s in most places (except for a few locations that are protected from rapid warm air intrusions such as North Bend).

By 5 PM Sunday, the snow level estimation product from UW Atmospheric Sciences’ Snow Watch website showed temperatures in the 40s up to 1,900 ft elevation and a freezing level above 3,000 ft in the Seattle area.

It’s nearly impossible to quickly get the snow level back to the surface when that deep of a warm air mass moves in.

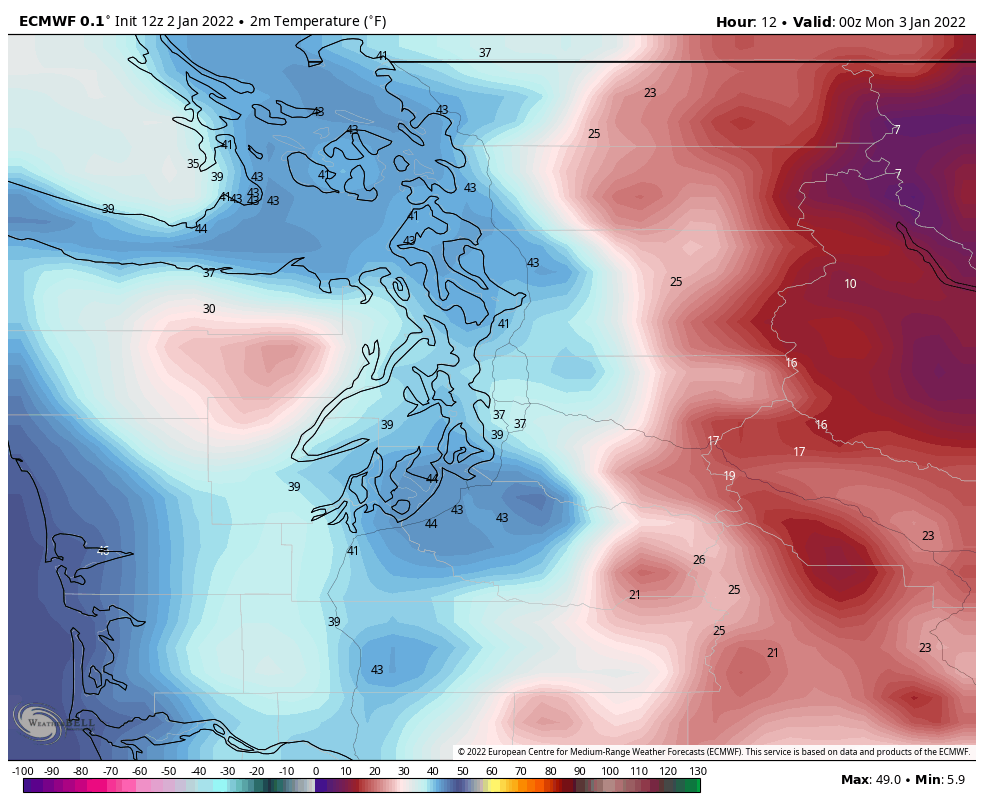

Not surprisingly, the global models did not expect temperatures to warm up to the low-40s in areas that were expected to receive snow a few hours later. The ECMWF expected the temperature to remain in the upper-30s in the central Sound.

The reason for the colder temperatures in the central Sound was the expectation in the global models that easterly winds would continue to supply cold air to the central sound via the Cascade passes.

There was plenty of cold air available — the temperature was only 14°F at Snoqualmie Pass at this time.

However, the easterly winds never really materialized as expected in the global models. The main reason is likely the lower horizontal resolution of global models — 9 km for the ECMWF and 13 km for the GFS. Even as global model resolution has improved substantially, 9-13 km is not enough to resolve the finer details of our mountain passes.

In contrast, the 3 km HRRR model showed southerly winds dominating over the central Sound on Sunday evening.

The highest resolution model we have, the1.33 km UW-WRF, seemed to do the best job resolving both the localized easterlies in the passes and the southerlies in the central Sound.

Easterly winds were occasionally observed last night both at Sea-Tac airport and in the Seattle area. However, they were neither strong enough nor sustained enough to drop the temperature below 37°F or so.

Heavy precipitation rates

If the winds were the only issue, I think the mesoscale models would have nailed the forecast and there would have been no snow below 1,000 ft except around North Bend, Gold Bar, and along the eastern slopes of the Olympics.

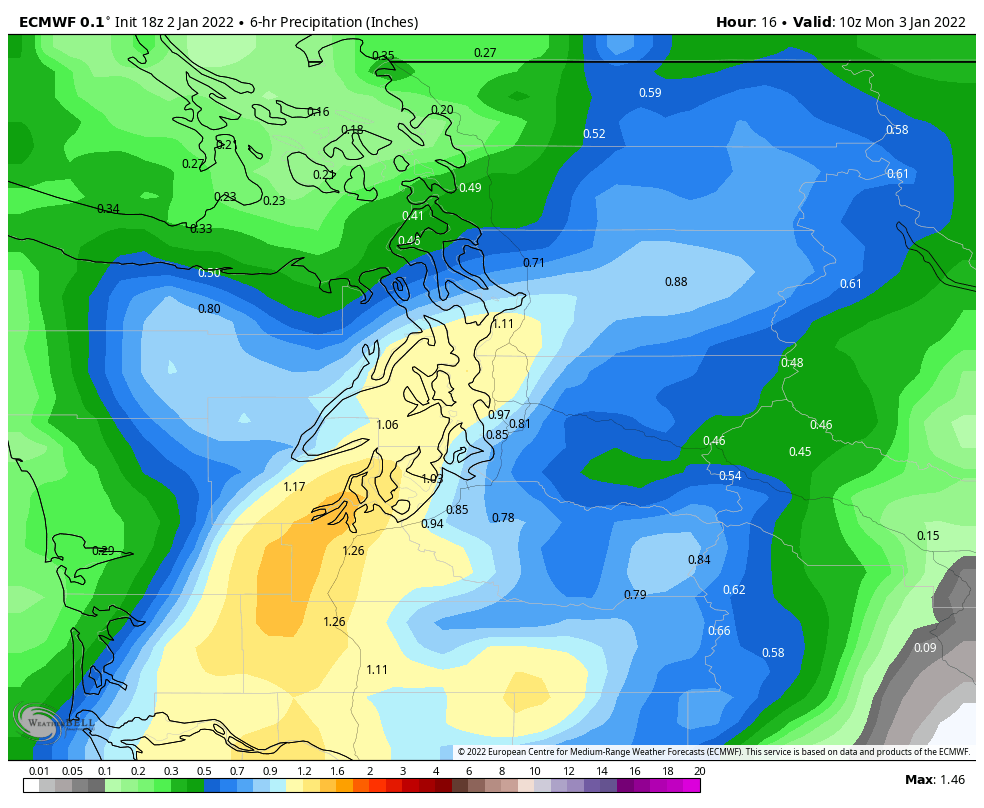

In this case there was another factor at play — the heavy precipitation rates within the front itself. The ECMWF showed 6-hour precipitation totals from (8 PM – 2 AM) of over an inch in many of the areas that received snow. This forecast was largely correct.

Heavy precipitation can lower snow levels in two ways. One process is a “dynamic” lowering of the melting level caused by strong rising motion in strong weather systems such as convective updrafts and strong fronts. As air rises, it expands and cools, lowering the temperature. The observed lightning last night was another indicator of strong rising motion within the frontal boundary.

The second process is a “diabatic cooling” of the air caused by the latent energy required to melt of ice/snow into rain around the melting level. The diabatic cooling process goes hand-in-hand with the dynamic cooling since it is the rising motion that leads to large quantities of ice/snow forming in the cloud.

Here’s one time-height radar example from Gatlin et al. (2018) showing how the radar bright band (i.e. the radar signature caused by melting ice/snow) lowers and thickens in periods of heavier precipitation. The melting level is initially around 2.1 km in this image but it drops by several hundred meters or more in the heavier precipitation.

For those of us that did not see snowfall last night, the large rain drops generated by this type of weather system were readily apparent. The giant aggregate snowflakes mixed with rain in other locations indicated that the radar bright band had lowered to the surface.

As a whole, weather models are excellent at resolving the cooling associated with heavy precipitation. I doubt that the heavy precipitation was the source of model error last night. But the heavy precipitation rates did briefly drop the snow levels below 500 ft elevation north of Seattle.

Putting it all together

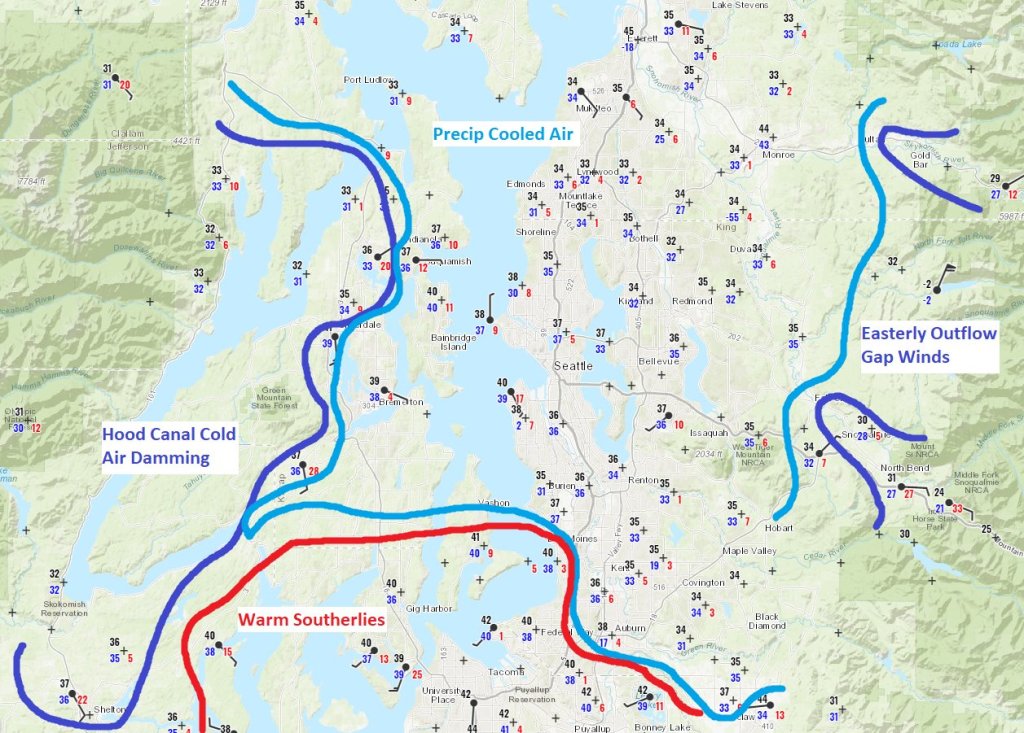

The surface map below drawn by Aidan Teall beautifully shows all of the pieces as they came together last night around 10 PM. I added the image below the tweet so that it is easier to see the temperatures and wind barbs.

The areas that saw the most snowfall are shown in dark blue — these regions had remnant cold air (Kitsap) or a nearby source of additional cold air (Snoqualmie and Stevens passes). The light blue area saw snow generally above 500 ft elevation (slightly lower within the heavier precipitation band) thanks to the cooling processes described above. And the red area remained in the 40s as a result of continual southerly winds.

What lessons can be learned?

Because the PNW is a coastal region of complex terrain, it is often near-impossible for global models to handle rapid temperature changes. The combination of an ‘end-of-cold-spell’ warming event with a powerful and dynamic frontal passage was bound to produce a difficult forecast.

In this case, no model got it entirely right. The mesoscale models had a better depiction of the easterly vs. southerly winds, but they did not predict the lowering of the snow level to below 500′ over large portions of King and Snohomish counties. The global models seemed to better anticipate the lower snow levels, but they were too aggressive in bringing cold air eastward through the passes.

In many cases we can get away with taking model snow maps at face value. In dynamic events like this frontal passage it is necessary to look closer at the meteorological processes involved to understand why the models disagree and what they might be getting wrong.

Thanks for the thorough discussion of some of the limitations in models, which reinforces the adage to guard against falling love with your favorite model. There is still some room and need for judgment. I noticed that NWS forecasters seem more reluctant to make a forecast of an extreme event based on a model prediction, particularly when the potential event is some distance away. Maybe this is just an application of Bayesian analysis, which is really beyond my capability. I noticed that yesterday, the NWS had a high wind warning for Whatcom County, which they have since taken down. It seems that at this moment, there is quite a lot of uncertainty about how much more snow we will get, if any, in the short term.

LikeLike

I would say that NWS was off quite a bit on its prediction for Bellingham for Wednesday evening/Thursday morning. The last forecast was 2-4″ of snow with rain and warming above freezing in the middle of the night. Instead, I would estimate we got 6-9″ of snow (some of the depth may be from drifting). The snow is not as dry as the prior snow event. Temperatures never got above the mid 20’s last night and we are currently at 26F and still waiting for the warm-up ( hopefully without significant freezing rain). I suspect the northern part of Whatcom County is going to take quite a bit longer to warm-up

LikeLike